nVentic Big Pharma inventory trends benchmarking report 2021

To see the latest version of this DIO benchmark, see our latest white paper: nVentic Big Pharma inventory trends benchmarking report 2024

It has been quite a year for the whole of the medical supply chain, but what, if anything, has the Covid-19 pandemic taught us about the inventories of the big pharmaceutical manufacturers? In this, our annual benchmark of big pharma inventories, we will have a look at what the data is telling us.

But before diving into the numbers, one thing is hopefully clear already: the global pharmaceutical supply chain has proven itself remarkably resilient over the past 12 months. A number of localized issues notwithstanding, supply chain professionals across the world have done a great job of keeping essential medicines moving.

Who would have thought, 12 months ago, that even one, let alone several vaccines to treat Covid would be developed, launched and being rolled out at speed by now? This has not happened without herculean efforts, not least on the part of the supply chain specialists who have helped make it possible. And in the meantime, despite limited freight capacity, volatile demand patterns, restricted working practices and stockpiling in various parts of the supply chain, supply of other pharmaceutical products has continued more or less uninterrupted.

For anyone who has worked in pharma supply chain this should perhaps not be a surprise. The industry is very conscious of the life-saving or life-enhancing properties of its products and has well-devised strategies to avoid sudden shortages, including multiple sources of supply and, yes, inventories.

So what has all this meant for inventories held by the big pharma companies themselves? How well provisioned were they going into the pandemic, what have the trends been during the year, and what does the situation look like now?

But before diving into the numbers, one thing is hopefully clear already: the global pharmaceutical supply chain has proven itself remarkably resilient over the past 12 months. A number of localized issues notwithstanding, supply chain professionals across the world have done a great job of keeping essential medicines moving.

Who would have thought, 12 months ago, that even one, let alone several vaccines to treat Covid would be developed, launched and being rolled out at speed by now? This has not happened without herculean efforts, not least on the part of the supply chain specialists who have helped make it possible. And in the meantime, despite limited freight capacity, volatile demand patterns, restricted working practices and stockpiling in various parts of the supply chain, supply of other pharmaceutical products has continued more or less uninterrupted.

For anyone who has worked in pharma supply chain this should perhaps not be a surprise. The industry is very conscious of the life-saving or life-enhancing properties of its products and has well-devised strategies to avoid sudden shortages, including multiple sources of supply and, yes, inventories.

So what has all this meant for inventories held by the big pharma companies themselves? How well provisioned were they going into the pandemic, what have the trends been during the year, and what does the situation look like now?

Hindsight 2020

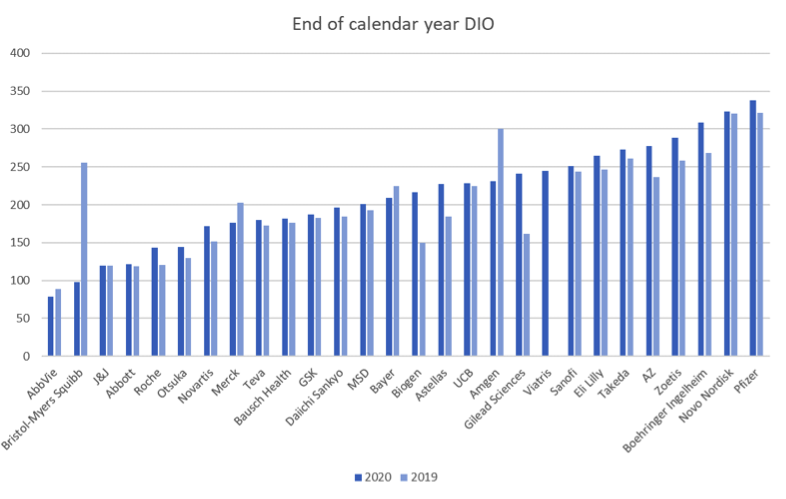

The big pharmaceutical manufacturers entered 2020 with substantial inventories, as we commented last year. Median for our benchmark was 193 days, a bit more than 6 months.

One of the benefits of a large inventory buffer, if of the right products, is that it allows you to absorb supply disruption and demand increases up to a point, and to this extent it is an asset. On the other hand, in instances where demand is down and your inventories are perishable, too much of the wrong inventory quickly becomes a liability. Both effects have been experienced during 2020.

No two companies have exactly the same product mix and so inevitably none was impacted in exactly the same way as any other, but from a survey of their annual reports and press releases a number of macro-trends emerge.

The first quarter of 2020 saw an increase in sales, as initial concerns about the pandemic and its impact led to stockpiling across the various channels that the manufacturers supply – the hospitals, clinics, pharmacies and wholesalers. However, with a few exceptions, this increase in sales was easily covered by existing inventories.

Q2 and Q3 2020, on the contrary, saw a marked softening in demand. Partly this was just a natural lull after the channel stockpiling in Q1. However, another factor in play was a reduction in elective care. As lockdowns discouraged people from visiting the doctors, demand for a lot of non-Covid-related drugs fell. Therefore, over Q2 and Q3 inventories grew.

In Q4 sales recovered, but at the end of 2020 inventories remain somewhat up on the previous year, although not significantly so. For the companies in our benchmark where a comparison is meaningful, median DIO is up 4% year on year, to 201 days.

One of the benefits of a large inventory buffer, if of the right products, is that it allows you to absorb supply disruption and demand increases up to a point, and to this extent it is an asset. On the other hand, in instances where demand is down and your inventories are perishable, too much of the wrong inventory quickly becomes a liability. Both effects have been experienced during 2020.

No two companies have exactly the same product mix and so inevitably none was impacted in exactly the same way as any other, but from a survey of their annual reports and press releases a number of macro-trends emerge.

The first quarter of 2020 saw an increase in sales, as initial concerns about the pandemic and its impact led to stockpiling across the various channels that the manufacturers supply – the hospitals, clinics, pharmacies and wholesalers. However, with a few exceptions, this increase in sales was easily covered by existing inventories.

Q2 and Q3 2020, on the contrary, saw a marked softening in demand. Partly this was just a natural lull after the channel stockpiling in Q1. However, another factor in play was a reduction in elective care. As lockdowns discouraged people from visiting the doctors, demand for a lot of non-Covid-related drugs fell. Therefore, over Q2 and Q3 inventories grew.

In Q4 sales recovered, but at the end of 2020 inventories remain somewhat up on the previous year, although not significantly so. For the companies in our benchmark where a comparison is meaningful, median DIO is up 4% year on year, to 201 days.

Days Inventory Outstanding (DIO) = inventory value/(cost of sales/365). See also the technical notes at the end of this article.

The trend over 2020 as a whole was thus a (small) increase in inventories. 22 of the companies in this benchmark saw their inventories increase whilst only 5 saw them decrease and at least 2 of those 5 can be attributed to one-off events.

Several companies mention an intention to increase raw materials to protect against potential supply disturbance, but in fact, of the companies who have published the splits at the year end, only half show a DIO increase in raw materials whereas two thirds show an increase in WIP and/or finished goods. If anything, this suggests declining sales have had as big an impact on inventories as planned increases, although given the macro-environment and the long lead times involved, this is not surprising. It is hard to turn a tanker at speed.

Of course, this high-level view needs to be understood for what it is. Relatively small aggregate percentage changes hide much larger swings at a product level. While demand is sky-high for products used to prevent or treat Covid, other therapeutic areas have seen considerable declines. Several companies have commented on increases in write offs of excess and obsolete (E&O) inventory for just this reason.

Several companies mention an intention to increase raw materials to protect against potential supply disturbance, but in fact, of the companies who have published the splits at the year end, only half show a DIO increase in raw materials whereas two thirds show an increase in WIP and/or finished goods. If anything, this suggests declining sales have had as big an impact on inventories as planned increases, although given the macro-environment and the long lead times involved, this is not surprising. It is hard to turn a tanker at speed.

Of course, this high-level view needs to be understood for what it is. Relatively small aggregate percentage changes hide much larger swings at a product level. While demand is sky-high for products used to prevent or treat Covid, other therapeutic areas have seen considerable declines. Several companies have commented on increases in write offs of excess and obsolete (E&O) inventory for just this reason.

Outlook

Despite the tremendous success of the vaccines to date, the pandemic is far from over. In the short term there is still considerable uncertainty. Lockdowns, with their impact on new patient starts, clinical trials and overall supply chains, remain one of the most effective barriers to the virus. Vaccines and vaccination will continue to put supply chains under strain as capacity and resources are focused there. The development of new variants and their resistance to the vaccines remains to be seen. Many medicines are still being tested as potential treatments for Covid and could suddenly see a surge in demand if they are found to be effective. In short, it is likely to take some time before anything like normality returns to the market.

The judicious building of strategic inventories to ensure supply will continue to be an important lever. Inventory optimization is not the enemy of inventory, just the enemy of the wrong inventory. Even as pharmaceutical companies move to ensure the supply of their critical medicines, they also need to make sure that resources and capacity are not wasted on excess inventory. The billions of euros written off due to obsolescence each year can never be eradicated entirely if we want to continue to ensure high availability of medicines, but the industry can do better on this measure.

It is to be hoped that there are also some lasting benefits to be gained from the industry’s reaction to the pandemic. One of the biggest obstacles to better inventory levels is the long lead times taken to manufacture pharmaceutical products. In the last year necessity has truly been the mother of invention in this respect, as lead times have been driven down for several products in high demand. This needs to be an area of focus for as many products as possible. Reducing lead times without compromising on stability makes supply chains more agile and responsive and reduces the need to build large buffers of perishable medicines.

There are also various longer-term considerations that are likely to affect global pharmaceutical supply chains in the coming years.

2020 was a breakthrough year for mRNA technology. The wider field of genetic treatments, long promising, could start to change the focus and mix of technology used by the industry overall. While presenting a number of production challenges that have only recently been overcome, mRNA technology should in principle facilitate shorter manufacturing cycles because it is not dependent on cell cultures. Manufacturing processes should also be able to be repurposed more easily for new treatments.

Another set of changes potentially coming down the tracks are political. At the time of writing, the US has a 100-day review of its drug supply chain underway, while the EU published a new Pharmaceutical Strategy for Europe back in November. Both address the topic of security of supply, and could lead to requirements to onshore or near-shore certain types of production. This might have mixed results for supply chains. Excessive reshoring could actually lead to increased concentration risks, but if done proportionately it could have benefits, including in reducing lead times for raw materials which are currently predominantly manufactured in China and India.

In summary, while continuity of supply will continue as always to be the top priority for the big pharmaceutical companies, the high levels of interest and scrutiny in supply chains also represent an opportunity to drive improvement in areas in which the industry has historically underperformed, including inventories. Will 2021 be the year when the corner is turned?

The judicious building of strategic inventories to ensure supply will continue to be an important lever. Inventory optimization is not the enemy of inventory, just the enemy of the wrong inventory. Even as pharmaceutical companies move to ensure the supply of their critical medicines, they also need to make sure that resources and capacity are not wasted on excess inventory. The billions of euros written off due to obsolescence each year can never be eradicated entirely if we want to continue to ensure high availability of medicines, but the industry can do better on this measure.

It is to be hoped that there are also some lasting benefits to be gained from the industry’s reaction to the pandemic. One of the biggest obstacles to better inventory levels is the long lead times taken to manufacture pharmaceutical products. In the last year necessity has truly been the mother of invention in this respect, as lead times have been driven down for several products in high demand. This needs to be an area of focus for as many products as possible. Reducing lead times without compromising on stability makes supply chains more agile and responsive and reduces the need to build large buffers of perishable medicines.

There are also various longer-term considerations that are likely to affect global pharmaceutical supply chains in the coming years.

2020 was a breakthrough year for mRNA technology. The wider field of genetic treatments, long promising, could start to change the focus and mix of technology used by the industry overall. While presenting a number of production challenges that have only recently been overcome, mRNA technology should in principle facilitate shorter manufacturing cycles because it is not dependent on cell cultures. Manufacturing processes should also be able to be repurposed more easily for new treatments.

Another set of changes potentially coming down the tracks are political. At the time of writing, the US has a 100-day review of its drug supply chain underway, while the EU published a new Pharmaceutical Strategy for Europe back in November. Both address the topic of security of supply, and could lead to requirements to onshore or near-shore certain types of production. This might have mixed results for supply chains. Excessive reshoring could actually lead to increased concentration risks, but if done proportionately it could have benefits, including in reducing lead times for raw materials which are currently predominantly manufactured in China and India.

In summary, while continuity of supply will continue as always to be the top priority for the big pharmaceutical companies, the high levels of interest and scrutiny in supply chains also represent an opportunity to drive improvement in areas in which the industry has historically underperformed, including inventories. Will 2021 be the year when the corner is turned?

Technical Notes

Benchmark reports for 2018, 2019 and 2020 can be found on our website.

For a fuller discussion of DIO as a metric, see our Ultimate guide to DIO. All figures from published corporate reports/filings.

Unlike in previous years, this year we have used figures for calendar 2019 and 2020 for all firms, including those whose financial years are not the calendar years, i.e. Daiichi Sankyo, Takeda and Astellas. This enabled seasonal effects related to the pandemic to be seen more easily.

Like in previous years, we have used an estimate of Boehringer Ingelheim’s cost of sales, which they do not publish.

Acquisitions have a misleading effect on DIO, since acquired inventory is stepped up to fair value, which reflects the acquisition cost, not the production cost that the rest of the inventory is mostly valued at. This fair value is amortized over time, but creates an artificial bump in DIO in the period immediately following the acquisition which can take a time to unwind. The cost of the acquisition itself, if amortized quickly, can also have the opposite effect on DIO, as is evident with Amgen in 2020, when its acquisition of Otezla saw an increase in inventories of less than 10% but annual cost of sales up by 41%, substantially driven by the acquisition costs.

During the period considered (2019 and 2020), the following major acquisitions had a material effect on DIO numbers: Bristol Myers Squibb’s acquisition of Celgene, Gilead’s acquisition of Immunomedics, Amgen’s acquisition of Otezla.

Abbvie’s acquisition of Allergan, because it closed mid-year, is not so visible in the end of year figures, even though they anticipate it will take a year to amortize the $1.2bn step up in inventory value.

Biogen also has a noticeable increase in inventories from 2019 to 2020. This seems to be at least partly due to the capitalization of nearly $100m of pre-launch aducanumab inventory at the end of 2020.

Viatris launched in Q4 2020, formed of Mylan and Upjohn. As these two firms had very different inventory profiles, neither makes a good year-on-year point of comparison for Viatris.

Benchmark reports for 2018, 2019 and 2020 can be found on our website.

For a fuller discussion of DIO as a metric, see our Ultimate guide to DIO. All figures from published corporate reports/filings.

Unlike in previous years, this year we have used figures for calendar 2019 and 2020 for all firms, including those whose financial years are not the calendar years, i.e. Daiichi Sankyo, Takeda and Astellas. This enabled seasonal effects related to the pandemic to be seen more easily.

Like in previous years, we have used an estimate of Boehringer Ingelheim’s cost of sales, which they do not publish.

Acquisitions have a misleading effect on DIO, since acquired inventory is stepped up to fair value, which reflects the acquisition cost, not the production cost that the rest of the inventory is mostly valued at. This fair value is amortized over time, but creates an artificial bump in DIO in the period immediately following the acquisition which can take a time to unwind. The cost of the acquisition itself, if amortized quickly, can also have the opposite effect on DIO, as is evident with Amgen in 2020, when its acquisition of Otezla saw an increase in inventories of less than 10% but annual cost of sales up by 41%, substantially driven by the acquisition costs.

During the period considered (2019 and 2020), the following major acquisitions had a material effect on DIO numbers: Bristol Myers Squibb’s acquisition of Celgene, Gilead’s acquisition of Immunomedics, Amgen’s acquisition of Otezla.

Abbvie’s acquisition of Allergan, because it closed mid-year, is not so visible in the end of year figures, even though they anticipate it will take a year to amortize the $1.2bn step up in inventory value.

Biogen also has a noticeable increase in inventories from 2019 to 2020. This seems to be at least partly due to the capitalization of nearly $100m of pre-launch aducanumab inventory at the end of 2020.

Viatris launched in Q4 2020, formed of Mylan and Upjohn. As these two firms had very different inventory profiles, neither makes a good year-on-year point of comparison for Viatris.

Would you like to receive more content like this, direct to your inbox? We publish white papers on a range of supply chain topics approximately once every one to two months. Subscribe below and we will notify you of new content. Unsubscribe at any time.

For our other articles on supply chain responses to Covid-19, see the relevant section on our Insights page.

Would you like to talk to one of our experts? Contact us