Inventory write offs in pharmaceutical manufacturing

Public health and the environment are areas of high concern. These two topics overlap in the waste generated by the pharmaceutical industry. In this article we want to consider one particular type of waste, which is excess and obsolete (E&O) inventory: the medicines destroyed because surplus to requirements or out of date.

And while waste of this kind is generated at different points in the supply chain, from raw material production to unused medicines discarded by patients, we are going to focus on the pharmaceutical manufacturers themselves.

How big an issue is this, what causes it and can it be avoided?

How much is scrapped each year?

While sustainability reports are becoming ever-more common and comprehensive, waste in the sense of surplus products does not yet seem to be on the radar. Companies report on important metrics like energy and water consumption, plus CO2 emissions and waste (in the sense of by-products from the manufacturing process), but not yet how much of those relate to products that end up being scrapped.

Financial reports can sometimes give an indication of the scale of the issue, but not necessarily entirely transparently. Some companies report on inventories written off for obsolescence, excess or unmarketability, which is probably as close as we can get to the number that interests us, although even in this case any scrap due to excess is bundled with quality excursions.

Frequently, instead of write offs (where the full value of inventory is permanently removed from the balance sheet), companies report write downs. A write down could be due to a need to discount medicines, to the extent the net realizable value becomes less than the production cost. Or it could be a temporary measure to reflect the risk of inventory becoming worthless. This is particularly relevant to pharmaceuticals, where new medicines are often produced in large quantities before regulatory approval is achieved. In this case a write down might subsequently be reversed.

A survey of annual reports also turns up provisions for inventory impairment, which is where companies estimate in advance how much inventory will be written down or written off and make allowance for it in their balance sheets. All such decisions also have implications for tax, as both tax assets and liabilities can be deferred.

And finally, you also frequently find no mention of inventory impairment at all. Nearly half of the 28 big pharma companies in nVentic’s 2023 big pharma inventory benchmark report make no mention of inventory write offs, although one can be sure that they too destroy unused inventory each year.

Where inventory is scrapped, the cost normally passes through cost of sales (and inventory write downs treated as an expense is one variant of the numbers reported) but this is not the only possible treatment. Where inventory is built up and destroyed before product launch the expense can be charged to R&D rather than cost of sales.

In summary, therefore, it is very hard to ascertain with any degree of accuracy how much medicine is scrapped by the big pharma manufacturers each year from their annual reports and since the ones who do report at least some figures use different variations (impairment vs write off vs write down vs provisions, treated as an expense for cost of sales or not), we cannot meaningfully compare the companies amongst themselves in this respect either.

Looking at the numbers that are reported, however, which range from under 0.5% to over 10% of inventory sold each year, and admitting all of the uncertainty concerning inclusions and exclusions outlined above, it would appear that on average ~4% (based on 2022 figures) of all inventory produced is written off. Discussions with a number of companies on this list suggest a figure in this ballpark.

While 4% may not sound like much as a percentage, certainly not compared to something like waste in the food industry, it represents over $11bn (production cost) of medicines destroyed each year just for these 28 companies.

One can assume that any company would rather not have to destroy a product it has put so much time, effort and money into producing, so what are the root causes of this waste and (how) can we tell if 4% is good or bad?

The causes of scrap

A certain amount of obsolescence is inevitable in almost all supply chains, since forecasts are never perfect and most products reach a point where no one wants to buy them anymore. The problem is particularly acute for perishable products like medicines which have a definite shelf life beyond which they cannot be used and which demand high availability because they are essential for the preservation of life or quality of life.

Some of the main root causes for E&O inventory in pharmaceuticals are:

And while waste of this kind is generated at different points in the supply chain, from raw material production to unused medicines discarded by patients, we are going to focus on the pharmaceutical manufacturers themselves.

How big an issue is this, what causes it and can it be avoided?

How much is scrapped each year?

While sustainability reports are becoming ever-more common and comprehensive, waste in the sense of surplus products does not yet seem to be on the radar. Companies report on important metrics like energy and water consumption, plus CO2 emissions and waste (in the sense of by-products from the manufacturing process), but not yet how much of those relate to products that end up being scrapped.

Financial reports can sometimes give an indication of the scale of the issue, but not necessarily entirely transparently. Some companies report on inventories written off for obsolescence, excess or unmarketability, which is probably as close as we can get to the number that interests us, although even in this case any scrap due to excess is bundled with quality excursions.

Frequently, instead of write offs (where the full value of inventory is permanently removed from the balance sheet), companies report write downs. A write down could be due to a need to discount medicines, to the extent the net realizable value becomes less than the production cost. Or it could be a temporary measure to reflect the risk of inventory becoming worthless. This is particularly relevant to pharmaceuticals, where new medicines are often produced in large quantities before regulatory approval is achieved. In this case a write down might subsequently be reversed.

A survey of annual reports also turns up provisions for inventory impairment, which is where companies estimate in advance how much inventory will be written down or written off and make allowance for it in their balance sheets. All such decisions also have implications for tax, as both tax assets and liabilities can be deferred.

And finally, you also frequently find no mention of inventory impairment at all. Nearly half of the 28 big pharma companies in nVentic’s 2023 big pharma inventory benchmark report make no mention of inventory write offs, although one can be sure that they too destroy unused inventory each year.

Where inventory is scrapped, the cost normally passes through cost of sales (and inventory write downs treated as an expense is one variant of the numbers reported) but this is not the only possible treatment. Where inventory is built up and destroyed before product launch the expense can be charged to R&D rather than cost of sales.

In summary, therefore, it is very hard to ascertain with any degree of accuracy how much medicine is scrapped by the big pharma manufacturers each year from their annual reports and since the ones who do report at least some figures use different variations (impairment vs write off vs write down vs provisions, treated as an expense for cost of sales or not), we cannot meaningfully compare the companies amongst themselves in this respect either.

Looking at the numbers that are reported, however, which range from under 0.5% to over 10% of inventory sold each year, and admitting all of the uncertainty concerning inclusions and exclusions outlined above, it would appear that on average ~4% (based on 2022 figures) of all inventory produced is written off. Discussions with a number of companies on this list suggest a figure in this ballpark.

While 4% may not sound like much as a percentage, certainly not compared to something like waste in the food industry, it represents over $11bn (production cost) of medicines destroyed each year just for these 28 companies.

One can assume that any company would rather not have to destroy a product it has put so much time, effort and money into producing, so what are the root causes of this waste and (how) can we tell if 4% is good or bad?

The causes of scrap

A certain amount of obsolescence is inevitable in almost all supply chains, since forecasts are never perfect and most products reach a point where no one wants to buy them anymore. The problem is particularly acute for perishable products like medicines which have a definite shelf life beyond which they cannot be used and which demand high availability because they are essential for the preservation of life or quality of life.

Some of the main root causes for E&O inventory in pharmaceuticals are:

- Perishability. Products reach the end of their shelf life before they can be used

- A very low risk approach to shelf life. Expiry dates represent the date up to which a pharmaceutical manufacturer will guarantee the safety and efficacy of a medicine. Various studies have shown that, depending of course on type of ingredients, forms and how medicines are stored, many medicines remain safe and even efficacious, although slowly declining from the date of manufacture, for many years past the expiry date, but regulations encourage the manufacturers to take minimal risks with reduced efficacy

- Patent protection. The limited time window during which a new medicine has patent protection puts commercial pressure on manufacturers to maximise sales, building sizeable inventories before actual sales begin

- Historically high profit margins have encouraged pharmaceutical manufacturers to be sales-led organisations with E&O inventory seen as just a cost of doing business. Avoidance of shortages at any cost tends to take precedence over efficiency in many cases

- Long lead times and large batch sizes reduce supply chain agility and make it hard for pharmaceutical companies to be responsive to changing market conditions

Different medicines will be affected by these different root causes to different extents, and this no doubt explains the range of inventory write offs, at least in part.

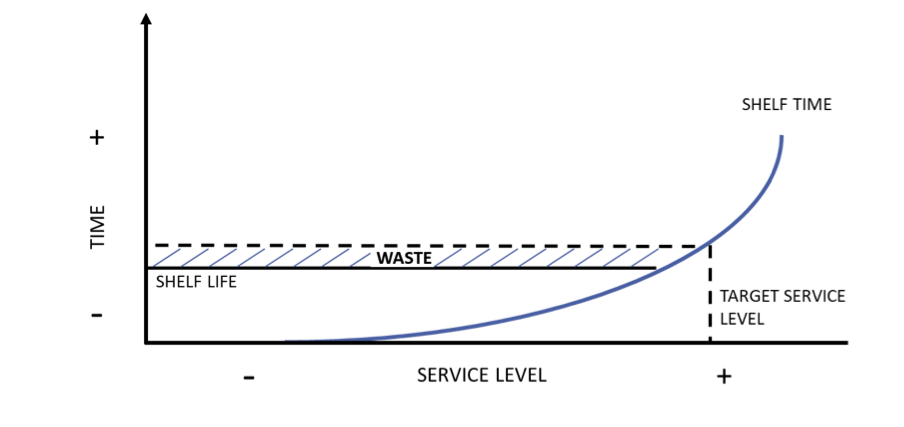

For items with a short shelf life, targeting very high service levels will actively generate waste. Average shelf time can be calculated from the target service level and where this is greater than the shelf life of the product, waste will consistently be generated (and can be calculated in advance):

For items with a short shelf life, targeting very high service levels will actively generate waste. Average shelf time can be calculated from the target service level and where this is greater than the shelf life of the product, waste will consistently be generated (and can be calculated in advance):

Figure 1: expected waste can be calculated from target service levels. The higher the service level, the longer each product will spend on the shelf on average. Where this exceeds the shelf life of the product, waste is generated

However, this is only likely to be the main driver of waste in items with very short shelf life, such as certain types of fresh produce where items perish within days. Even blood products last several weeks, while most drugs will last months or years.

Even given the very high service levels targeted for medicines, inventory write offs from pharmaceutical manufacturers are much more likely to indicate that volumes way in excess of demand have been produced. This means that of the 5 root causes listed above, the first two are unlikely to be the main drivers of waste at pharma manufacturers, so the other 3 should be the area of focus for improvement efforts. Let us concentrate on them as we consider whether a good proportion of the existing write offs can be avoided.

Can inventory write offs be avoided?

It bears repeating that pharmaceutical manufacturers are already naturally commercially motivated to avoid destroying inventory. No one is deliberately generating waste. But more could be done to reduce this type of waste. Let us look at the three main root causes in turn.

New product launches are surely one of the biggest headaches for pharmaceutical supply chains. Patent protection lasts 20 years from when the new molecular entity (NME) is filed. Of those 20, over 10 are taken up by research and development (1), meaning fewer than 10 remain for patent-protected sales. Since patent protection presents the opportunity for the highest margins in most drugs’ lifecycle, pressure is high to maximise sales during those remaining years.

Since lead times to source raw materials, commit capacity and build up the process are long, and since the regulatory process, which itself takes months, requires manufacturers to demonstrate they can produce at scale, production starts well before regulatory approval is assured. Where regulatory approval is denied, delayed, or dependent on changes, waste is very likely to be generated.

The thinking behind the patent protection regime makes sense. When a medical breakthrough is achieved, regulators want it to be available to patients as soon as possible. By putting a limit – 20 years – on patent protection, regulators ensure manufacturers are motivated to move quickly. Similarly, regulators want medicines to be affordable, so limiting the time a patent lasts allows cheaper alternatives to come onto the market relatively soon.

However, this time pressure has some undesirable side effects, of which E&O inventory is an obvious one. And this E&O inventory itself brings up the total cost of R&D, given the write offs of inventory prior to regulatory approval are usually charged to R&D.

One might validly ask whether a different regime could achieve the same ends while reducing the waste. For instance, giving manufacturers a fixed period of time, such as 8-10 years, post-approval to market new medicines before the patent expires and discouraging them from producing at scale (beyond what is required for the regulatory approval process itself) before the regulatory approval is formalised, might reduce some of the worst excesses in this area (although it must be said that the classic challenge of all new product launches – forecasting demand – is still likely to generate some E&O inventory).

Incentives for efficiency are another area worth exploring as this seems a persistent issue in pharmaceuticals. A McKinsey report from 2010 considered inventory optimization to be one of the biggest opportunities for pharma supply chains, estimating a minimum 25% reduction to be achievable. In fact, since then, in DIO terms those inventories have increased by over 10% instead!

While there is an obvious commercial incentive not to produce inventory that will not sell, the truth seems to be that overall margins are still adequate to allow manufacturers to remain nicely profitable while regularly scrapping a proportion of their inventories. Inventory optimization, for various reasons, is a technically challenging supply chain goal. However, if money itself is not sufficient reason to push much harder to reduce inventory write offs, perhaps the ever-greater imperative to reduce our collective environmental footprint could be. If pharmaceutical manufacturers had to start reporting, in a transparent and standard way, how much inventory they destroy each year – and the emissions related to it, then maybe efforts to find a better balance between high service levels and lean inventories would be increased.

In many cases, and pharmaceuticals is far from being alone in this, supply chain professionals already know they need less inventory, but they find it hard to prevail against sales voices in strategic planning processes such as Sales and Operations Planning (S&OP). A strong counterweight from a sustainability perspective might be beneficial in this situation.

Structural supply chain challenges, such as long lead times and large batch sizes, also represent potential for improvement, but are longer-term opportunities. Continuous and semi-continuous manufacturing present opportunities to move away from often large fixed batch sizes and finding or developing alternative raw material suppliers in-region also offers advantages.

Conclusions

There certainly appears to be an opportunity for pharmaceutical manufacturers to reduce the amount of E&O inventory they scrap each year and the environmental benefits of doing so are not insignificant. Perhaps a nudge in this direction can help these companies make a concerted effort to reduce it.

While society does have an expectation of very high availability of key medicines, we also have to keep in mind that there is a not insignificant opportunity cost in each medicine destroyed. That is money, time, effort and manufacturing capacity that could better have been employed in other directions.

And while we need to avoid the dangers of drawing too many conclusions of what could have been done with the wonderful benefits of hindsight, it is valid to question whether everything possible is being done to reduce this waste.

Even given the very high service levels targeted for medicines, inventory write offs from pharmaceutical manufacturers are much more likely to indicate that volumes way in excess of demand have been produced. This means that of the 5 root causes listed above, the first two are unlikely to be the main drivers of waste at pharma manufacturers, so the other 3 should be the area of focus for improvement efforts. Let us concentrate on them as we consider whether a good proportion of the existing write offs can be avoided.

Can inventory write offs be avoided?

It bears repeating that pharmaceutical manufacturers are already naturally commercially motivated to avoid destroying inventory. No one is deliberately generating waste. But more could be done to reduce this type of waste. Let us look at the three main root causes in turn.

New product launches are surely one of the biggest headaches for pharmaceutical supply chains. Patent protection lasts 20 years from when the new molecular entity (NME) is filed. Of those 20, over 10 are taken up by research and development (1), meaning fewer than 10 remain for patent-protected sales. Since patent protection presents the opportunity for the highest margins in most drugs’ lifecycle, pressure is high to maximise sales during those remaining years.

Since lead times to source raw materials, commit capacity and build up the process are long, and since the regulatory process, which itself takes months, requires manufacturers to demonstrate they can produce at scale, production starts well before regulatory approval is assured. Where regulatory approval is denied, delayed, or dependent on changes, waste is very likely to be generated.

The thinking behind the patent protection regime makes sense. When a medical breakthrough is achieved, regulators want it to be available to patients as soon as possible. By putting a limit – 20 years – on patent protection, regulators ensure manufacturers are motivated to move quickly. Similarly, regulators want medicines to be affordable, so limiting the time a patent lasts allows cheaper alternatives to come onto the market relatively soon.

However, this time pressure has some undesirable side effects, of which E&O inventory is an obvious one. And this E&O inventory itself brings up the total cost of R&D, given the write offs of inventory prior to regulatory approval are usually charged to R&D.

One might validly ask whether a different regime could achieve the same ends while reducing the waste. For instance, giving manufacturers a fixed period of time, such as 8-10 years, post-approval to market new medicines before the patent expires and discouraging them from producing at scale (beyond what is required for the regulatory approval process itself) before the regulatory approval is formalised, might reduce some of the worst excesses in this area (although it must be said that the classic challenge of all new product launches – forecasting demand – is still likely to generate some E&O inventory).

Incentives for efficiency are another area worth exploring as this seems a persistent issue in pharmaceuticals. A McKinsey report from 2010 considered inventory optimization to be one of the biggest opportunities for pharma supply chains, estimating a minimum 25% reduction to be achievable. In fact, since then, in DIO terms those inventories have increased by over 10% instead!

While there is an obvious commercial incentive not to produce inventory that will not sell, the truth seems to be that overall margins are still adequate to allow manufacturers to remain nicely profitable while regularly scrapping a proportion of their inventories. Inventory optimization, for various reasons, is a technically challenging supply chain goal. However, if money itself is not sufficient reason to push much harder to reduce inventory write offs, perhaps the ever-greater imperative to reduce our collective environmental footprint could be. If pharmaceutical manufacturers had to start reporting, in a transparent and standard way, how much inventory they destroy each year – and the emissions related to it, then maybe efforts to find a better balance between high service levels and lean inventories would be increased.

In many cases, and pharmaceuticals is far from being alone in this, supply chain professionals already know they need less inventory, but they find it hard to prevail against sales voices in strategic planning processes such as Sales and Operations Planning (S&OP). A strong counterweight from a sustainability perspective might be beneficial in this situation.

Structural supply chain challenges, such as long lead times and large batch sizes, also represent potential for improvement, but are longer-term opportunities. Continuous and semi-continuous manufacturing present opportunities to move away from often large fixed batch sizes and finding or developing alternative raw material suppliers in-region also offers advantages.

Conclusions

There certainly appears to be an opportunity for pharmaceutical manufacturers to reduce the amount of E&O inventory they scrap each year and the environmental benefits of doing so are not insignificant. Perhaps a nudge in this direction can help these companies make a concerted effort to reduce it.

While society does have an expectation of very high availability of key medicines, we also have to keep in mind that there is a not insignificant opportunity cost in each medicine destroyed. That is money, time, effort and manufacturing capacity that could better have been employed in other directions.

And while we need to avoid the dangers of drawing too many conclusions of what could have been done with the wonderful benefits of hindsight, it is valid to question whether everything possible is being done to reduce this waste.

In order to help reduce the amount of inventory destroyed through obsolescence each year, nVentic has joined the Sustainable Medicines Partnership, a not-for-profit private-public collaboration executing projects to make the use of medicines more sustainable and less wasteful. nVentic is leveraging its deep analytical expertise to help the SMP develop frameworks and approaches to help reduce excesses and improve availability of medicines.

For more information on the SMP, see www.yewmaker.com/smp

To discuss your challenges with excess and obsolete inventories, contact us.

For more information on the SMP, see www.yewmaker.com/smp

To discuss your challenges with excess and obsolete inventories, contact us.

Notes

1. Various estimates of average development times from first registering a new molecular entity to regulatory approval can be found, mostly in the range of 10 to 15 years, for example:

http://phrma-docs.phrma.org/sites/default/files/pdf/rd_brochure_022307.pdf

1. Various estimates of average development times from first registering a new molecular entity to regulatory approval can be found, mostly in the range of 10 to 15 years, for example:

http://phrma-docs.phrma.org/sites/default/files/pdf/rd_brochure_022307.pdf

Would you like to receive more content like this, direct to your inbox? We publish white papers on a range of supply chain topics approximately once every one to two months. Subscribe below and we will notify you of new content. Unsubscribe at any time.

Would you like to talk to one of our experts? Contact us